By Claudia Ostrop

Silk. Light, delicate, shiny. Noble. Whether as a woven fabric or yarn for knitting – silk is always special in some way. For thousands of years it has been one of the noblest and finest materials for textiles. We have put together some interesting information about this special material for you. Have fun while reading!

A Brief History of Silk

Numerous legends surround the history of silk production. Archaeological findings confirm that silk was already being used as a material around 3,000 BC. - in the Indus region (today Pakistan and parts of Afghanistan and India) and in China. Traces of fibres indicate the silk was made of the peacock moth Antheraea, a wild silk. Modern silk originated in China: it comes from the domesticated form of the silk moth Bombyx mori.

Of course, there are no exact dates, but according to legend, while drinking tea, Leizu von Xiling, wife of Emperor Huáng Dì, suddenly dropped a cocoon into the hot drink and it began to unravel, releasing a silk thread. Leizu then allegedly taught the Chinese people how to use the silkworm cocoons and how to make silk. That was around the 3rd millennium BC Christ. What is certain is that silk quickly became a coveted commodity. At times, it was even used as a means of payment in China.

Long-distance trade in Chinese silk already existed at the beginning of the Christian era. Silk was first transported to Europe by sea and later by land. During the Roman Empire, Chinese silk was worth its weight in gold! The so-called Silk Road probably had its origins in the first century AD, when trade caravans transported the coveted fabric from China to Rome.

Incidentally, the Chinese were forbidden, on pain of death, to take silkworms or their eggs out of the country. Of course, smuggling eventually succeeded and silk was also produced in Europe from the Middle Ages on. In 1754, Prussian King Frederick the Great even decreed the large-scale cultivation of mulberry trees in order to be able to have silk produced!

How is silk made?

Silk is the spinning fluid produced by silkworms with the special glands on their heads. This liquid becomes the thread that the larvae use to build the cocoons in which they pupate.

The Formation of the silk thread

The most commonly used, and best, silk is that of the silk moth Bombyx mori, which was bred specifically for silk production. After hatching, the caterpillars feed exclusively on the leaves of the white mulberry tree (hence the name "mulberry silk"). When the caterpillar hatches from the egg, it is 2 mm (0.078”) in size. Within 4 - 5 weeks, it quickly grows to almost 10 cm (4”) long.

Now it's time for it to pupate: It begins to weave itself into a silk thread. The silk substance, which consists of proteins, is secreted from a spinneret on the head of the caterpillar which immediately hardens into a thread in the air. With rhythmic head movements, the caterpillar wraps the thread around its body. What initially begins as a fluffy web is a solid cocoon of up to 300,000 entanglements (in only 2-3 day´s time). The thread is almost a kilometre long (0,62 miles)! After about a week in the egg-shaped cocoon, the caterpillar pupates. Eight days later, the mature moth hatches using a liquid to dissolve the cocoon at one point in order to crawl out.

The Extraction of the Silk Thread

If nature is allowed to take its course, the silk moth butterfly will destroy the cocoon when it hatches. The silk thread – which is the only natural endless fibre - would be "cut" into many individual pieces. In professional silk production, hatching is therefore anticipated.

On approximately the tenth day after they form, the cocoons are placed in hot water or treated with hot steam or hot air and the pupae die.

The cocoons are then soaked in warm water and the thread can be unwound. Usually, three to eight cocoons are wound up together. The silk glue creates a thread that can then be further processed in the silk spinning mill. For 250 g (8.81ounces) of silk thread you need around 1 kg (2.20 pounds) of cocoons, that is about 3,000 cocoons.

In Asia, the dead pupae are not simply disposed of; they are used as edible insects. Once the cocoons have been cooked, the pupae are used as food. In silk production elsewhere, they are used as fish feed.

What makes silk so special?

Silk is special in many ways: It cools in summer and warms in winter. How does that work? Silk has poor thermal conductivity. This means that in winter it doesn't let body heat escape easily, but rather keeps the warm air "trapped in." And in summer, it doesn't let the outside heat penetrate into the skin so quickly.

Silk has a very strong sheen and is extremely cuddly due to the fineness of the fibre. Silk can be dyed very well leading to high colour intensity. Because the fibres are so fine, woven fabrics made of silk can also be printed particularly well.

A single thread of silk is ten times thinner than a human hair. However, it has a third of the tensile strength of steel which allows it to withstand great pulling pressure making it one of the strongest natural fibres there is.

Silk is not just silk

There are many different types of silk: very delicate and smooth, irregularly thick, very shiny, or rather dull. It all depends on the caterpillar that spins the thread, and on the manufacturing method.

Mulberry silk - It is the highest quality and finest of all silks. The silk moth Bombyx mori, the only domesticated insect besides the honeybee, produces this beautiful endless fibre.

Tussah or Wild Silk - The cocoons of the wild tussah moth Antheraea are collected from trees and shrubs in the wild. Most of the time, the moths have already hatched, so that the threads are much shorter and more difficult to spin.

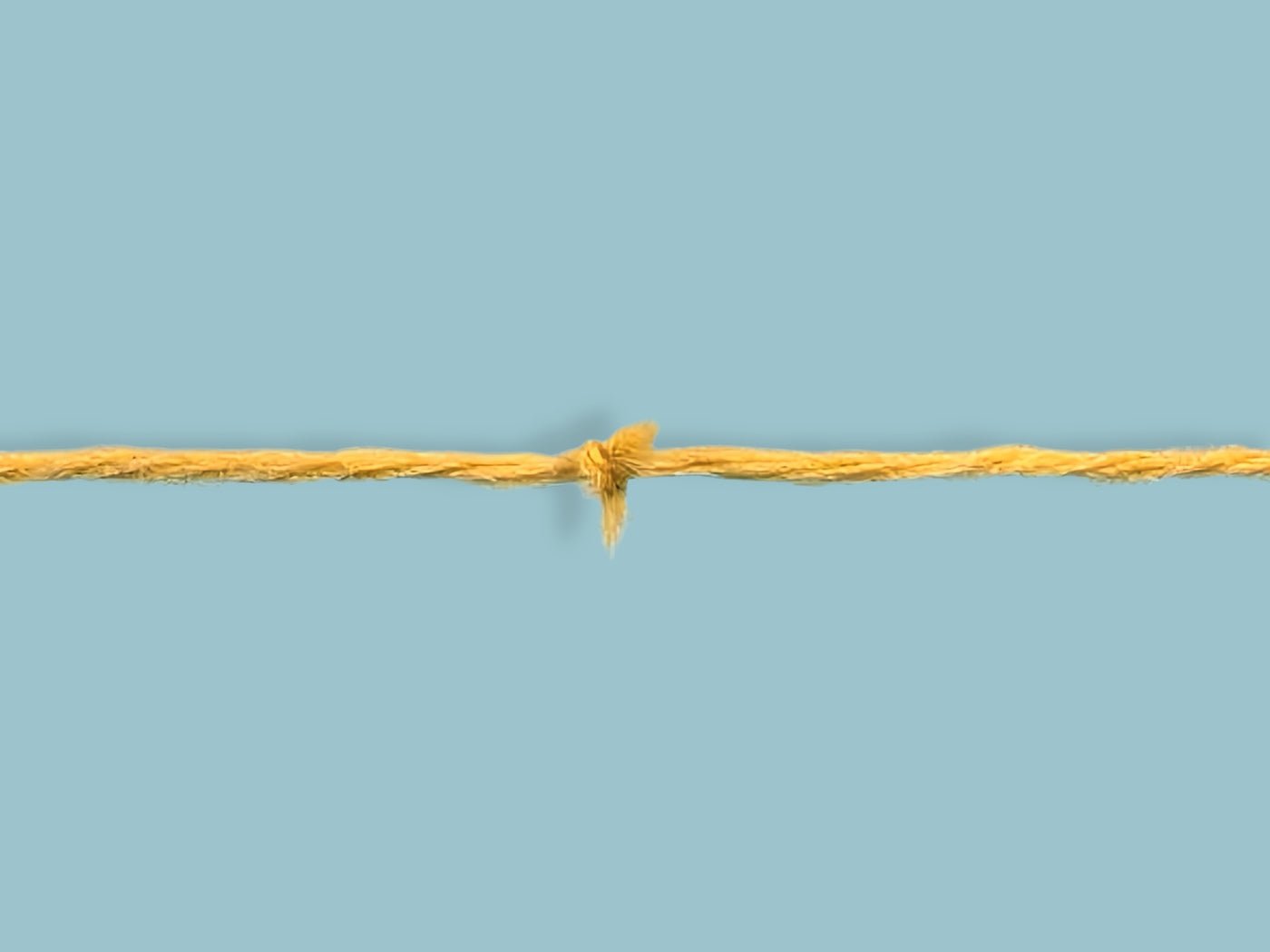

Bourette silk - This silk fibre is made from silk production waste. Particularly short pieces of fibre, mostly from the holding threads of the cocoons, which cannot be cleaned by the silk glue, result in a dull thread interspersed with knots.

Ahimsa silk - This silk is obtained by alternative outdoor breeding of the mulberry moth. The threads are not unwound from the cocoon until the moths have hatched. Because this causes the continuous thread to be severed many times, the processing is much more complex. However, the finished silk is much finer than that of wild silk, which is obtained using the same principle.

Care of Silk Garments

Textiles made of silk or with a silk content, regardless of whether they are woven or knitted, should best be washed carefully by hand in lukewarm water with a mild detergent, like our Organic Wool and Cashmere Detergent.

Textiles made of silk or with a silk content, regardless of whether they are woven or knitted, should best be washed carefully by hand in lukewarm water with a mild detergent, like our Organic Wool and Cashmere Detergent. Dry flat, preferably on a terry towel, to keep its shape.

Saffira is a yarn made from the finest merino and mulberry silk, pleasantly soft and suitable for all types of fine knitted pieces. The gauge of this mulesing-free merino wool is 17.5 microns, which falls into the finest category of "ultrafine" wool. Luxury for the skin!

Atlantis is one of the finest yarns in the Pascuali range. While the cashmere wool provides the yarn with softness and warmth, the mulberry silk is responsible for its delicate sheen. Together they make a lustrous, smooth yet incredibly soft yarn. The yarn is very fine yet robus. (No longer in assortment)

Manada combines fluffy kid mohair from Angora goats, shiny mulberry silk, precious yak wool and elastic merino wool (organic certified) into a fine yarn with tightly twisted threads and just the right amount of fleece.

Pinta is actually a sock yarn, but it is also ideal for all other knitting projects. The mulesing-free merino content warms in winter, the ramie ensures excellent moisture absorption and the mulberry silk content provides a very nice shine and high elasticity.